THE AI PROJECT: A SELF-ANNIHILATING GENRE

The rapid technological developments of the day call for commentary in new forms. It’s difficult to create an orderly essay on the topic of AI for the simple reason that things are evolving too quickly for one to get a grasp on anything beyond the thoughts of the present moment. Tomorrow’s developments will probably render today’s predictions obsolete though, seeing that the present is all we have, we are compelled to speak. Thus the idea of a self-annihilating genre, a work that aims not for posterity and permanence, but that accepts its disappearance with the coming of the next revelation. It is, I suspect, prophetic of the coming fate of humanity, whose present form seems fated, if not for extinction, then at least for transformation beyond its present condition.

I will not speak here about the dangers that are posed by the rapid rise of Artificial Intelligence. They are real - indeed, they may lead to our undoing - but there are other people more qualified than I to address such issues. I do not think, at this time, that AI is evolving toward sentience: it is designed to generate responses that are intelligible to us, but it knows not what it does, and has no intention, which would require a sense of its own existence, something it seems not to possess. But if I am mistaken, and if, in a real sense, AI learns, if a kind of consciousness eventually appears within it and, as some are predicting, comes to overwhelm and replace us, then perhaps this should be understood as the normal course of evolution - it is hubris to assume that humanity represents the end-goal of the universe. If we are the Titans, “they” are the gods.

Nor will I discuss in these pages the many ways in which AI may transform the world, in the foreseeable future, for the better, though I think that, if we can rise above personal ambition and the lust for power, an earthly paradise, free from disease, hunger, and drudgery may await us. My focus, instead, will be on those topics about which I have some real knowledge: music, literature, and art. (And in the end I will leap beyond the confines of the present moment and offer a glimpse at the ultimate consequences of this revolution in which, willy-nilly, we find ourselves immersed.)

Already, in its infancy, AI can construct fairly decent poems, songs, and paintings (though, like many fledgeling aesthetes, it struggles to rise above cliche). It’s better at synthesizing information to create well-organized, grammatically flawless essays. It can even provide a reliable evaluation for a work of literature or art that has not previously been studied. It should be borne in mind that, in responding to queries and requests, AI can only draw upon information already provided by humans.

Nevertheless, given its access to a vast repository of knowledge, its incredible operating speed, and the likelihood that technological evolution will continue to accelerate, it seems inevitable that, very shortly, AI will be capable of producing (what will seem to us) masterworks in the fields of literature, art, and music.

A tenth symphony by “Beethoven” - or, better, an original work that combines attributes of various artists to produce the effect of an original creative mind! And all of this faster than you can say Allegretto, and minus the struggle, the soul-searching, the angst we always believed necessary to such endeavors. Have we been fooling ourselves all along, romanticizing a process that may bear closer resemblance to that of AI than we would care to imagine?

How would we understand such developments? What could a painting, a piece of music, a poem, however lovely and compelling, possibly mean if it’s created without expressive intention? The sheer scope of things would also be daunting: in a minute we could request and receive a hundred sonatas, a dozen novels - a lifetime of exploration and discovery will be reduced to an ingenious, spontaneous formula.

While it might be tempting, in the face of such mindless magic, to throw up our hands and retire from the artistic labor and aesthetic ruminations, there remains a more constructive response to the emerging state of affairs: we can seek to work cooperatively with AI - we can use it as a tool and, in the process, reimagine the forms in which art is presented.

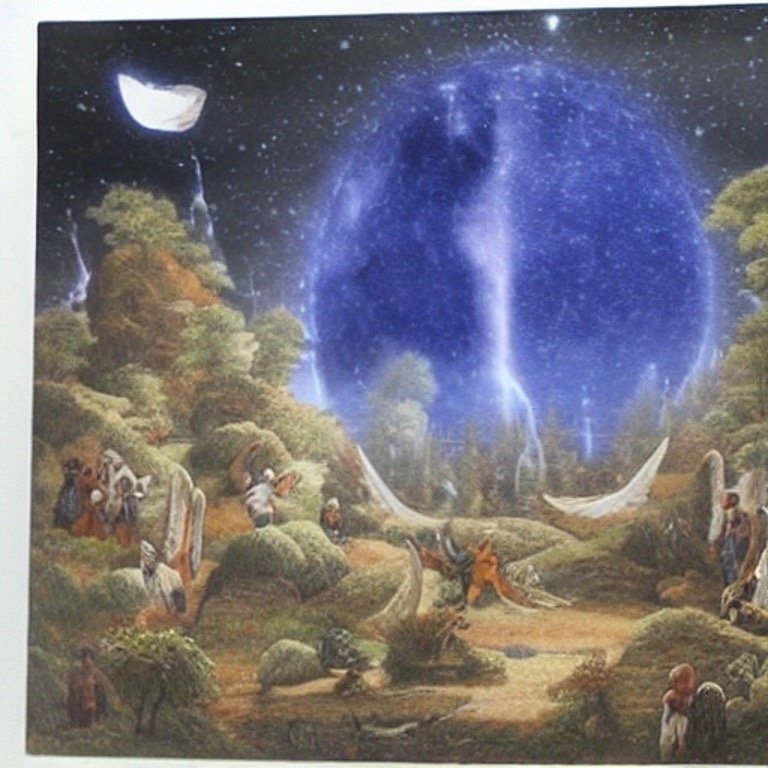

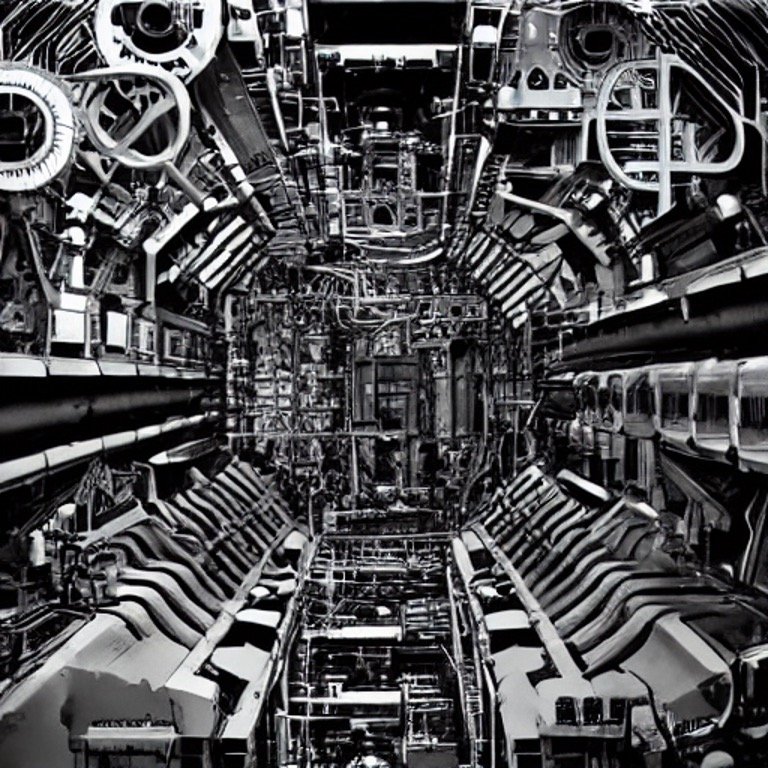

It is in this spirit that I have fashioned, in the realm of visual art, an example of the self-annihilating genre. Let us consider first that, traditionally, one views a series of artworks in a venue such as a gallery. This practice arose naturally from the fact that paintings are hung on walls in large spaces that allow for viewers to come and go. Similarly, the idea of hanging canvases on walls can be traced to a more fundamental assumption that a visual image is rendered on a two-dimensional rectangle, by which a scene or other image is suggested within an enclosed area.

But the days of galleries and canvases are disappearing, and will likely be replaced by virtual galleries such as the one I present here, while the notion of the finite, bounded image will ultimately lose meaning as well, and will give way to the immersive experience.

In attempting to work cooperatively with AI, and in an effort to utilize a mode of presentation appropriate to my endeavor, I took the following steps:

I chose verbal prompts from which deepai created visual images. I experimented with a wide variety of “titles” intended to suggest, alternately, the sublime (Feast of the Transfiguration, etc.), the ridiculous (The Emperor of Ice Cream, etc.), the enigmatic (Madonna with Pumpkin, etc), the humorous (Two Cans for Toucans, etc.), and more. In some cases I included the word “abstract” in the prompt. Occasionally I requested an image in the style of an actual human artist (Dali, Picasso, etc.).

For each prompt I repeated the request between two and twenty times, obtaining constantly varying results. Like a true artist, deepai seems not to repeat itself while, in the progression from one response to the next, I am unable to discover anything like a predictable pattern.

I determined that the images should change rapidly, in the manner of a slide-show, enhancing the sense of ephemerality crucial to the self-annihilating genre they inhabit.

The results are intriguing. If biological life is programmed to survive, artificial intelligence is programmed to serve. So AI strives with all its prodigious might to satisfy my prompts, but it never can truly understand what it is making. AI reveals a propensity for both virtuosity and (sometimes serendipitous) misunderstanding. As in a novel by Stanislaw Lem, I find myself face to face with what feels like a life-form so alien that true communication is impossible, though the failed attempts are haunting - riddles without answers, paths leading nowhere, dream-scenes from a non-existent unconscious…

********************************************************************************

As a postlude to the above, I would like to end by sharing a vision of our (perhaps not too distant) future, in which the present crises we approach will appear as quaint curiosities, in which all that we cherish will be as remote from the concerns of our descendents as are the concerns of the paleozoic age to us:

Humanity will merge with its technology. Those devices on which we presently store information ultimately will be integrated to our persons, and our access to that information will be instantaneous: think, and the answer is there! The need for remembering, for learning, the whole concept of education, will melt away into instant omniscience.

But if each of us knows everything, then what we know is the same. And since it is our limitations that define us, we will cease to be separate individuals. Identical in our omniscience, we will effectively be one - a vision proffered years ago by the religious philosopher Pierre Teillard de Chardin. And if by some miracle art had survived to this point, it would surely die here. For its purpose is communication, and in the world we are imagining that would be redundant.

Having everything, wanting for nothing, we would live in a state of desirelessness. There would no longer be a need for feet with which to travel, or hands with which to grasp. Virtually immortal as we’d probably be, I wonder: what would we do with all the time?

Of course we cannot fully answer that question any more than a jellyfish could imagine what it’s like to be human. But I will say this much: Grown beyond the concern merely to survive, with all our curiosities instantly appeased, our moral compunctions rendered moot, our creative instincts nullified by the technology we’ve made, we’d come face to face (as always, but as never before) with the riddle of existence. And perhaps we’d comprehend, in that exalted state, those enigmas that presently puzzle us. The scientist and inventor Arthur M. Young speaks of the goal of the universe as “creation coming to recognize itself.” Having mastered time and space, humanity (or humanity’s remote descendants) will come to the end of things and do what gods do - make the primal sacrifice: spreading themselves upon the wind in blissful surrender, so that the game may begin once again.

Epilogue

This is not for tomorrow. It is for today. In the radical isolation of the moment, I see at last not truth but fantasy, not destiny but freedom, not beauty but love.

(Even as I hasten each morning to the piano, with a feeling of vertigo, in order, before it’s too late, to write one last song…)

A song perhaps like this:

Oh, I met a man from Dover coming down the mountain path

With a satchel on his shoulder; on his arm a bonny lass.

But they smiled not at my greeting as they hurried on their way;

Then he turned and said, “This is the world’s last day.”

So they went down to the harbor where the long ships waiting lay,

And the captain gave the order and they sailed out of the bay.

And then one last time the church bell chimed: they turned upon its knell;

As they waved I thought, “This is the last farewell.”

They went down, they went down,

In the shadow of machines they went down.

Move aside, good Sir Walter; shake a leg now, Willy Boy.

Lay aside your grim remonstrance, leave Macbeth and leave Rob Roy,

And a hundred thousand lays unwritten ‘cross a thousand springs

That the young and lovestruck shepherds used to sing.

Yes and farewell, good Trelawne, farewell Meg and Peg and Kate;

Goodbye Penny, Benny, Seanny, by the flowering garden gate.

Though the thrush still gilds the myrtle there’ll be none to hear him sing

But a god-forsaken, heartless metal thing.

They go down, they go down,

In the shadow of machines they go down.

I cried, “‘Neath your shining armor you’re a hollow drum of tin!”

He said, “Father, I am but your next of kin.

And if something’s lost, then something’s gained- the master’s changed the tune,

So take your songs and your belongings and make room.”

We go down, we go down,

In the shade of the machines we go down.

Come down Jesus from your cross at last, there’s no one left to save,

All the saints and all the sinners have arisen from their graves

And been judged to be irrelevant - their heaven and their hell

Is to sleep beneath the shadow of machines.

two cans for toucans

Parakket with mangos

Madonna with pumpkin

jesus wtih beer

jesus with two beers

picasso

abstract

gnostic myth

kandinsky

orphan angel

orphan angels

the emperor of icecream

the emperor of icecream ii

orphan angel ii

orphan angels ii

dali

richter realistic

richter abstract

kline

hoffman

la belle dame sans merci

prompt forgotten

a tumult of mangos

soda-fish

soda-fish ii

feast of the transfiguration

feast of the transfiguration ii

ressurection

prompt forgotten

troubadour

troubadour ii

a tumult of mangos ii

in the shadow of machines

brave new world

dark eyes, bind me

honda

city of dreams

bardo

ressurection ii

soda-fish iii

bardo ii

mirth, memory’s antidote

ressurection iii

the end of time

ressurection IV

the transcendental railroad

gnostic myth ii

ressurection v

brave new world ii

dali ii